Current Study

Learning from Play: Mechanisms and Constraints

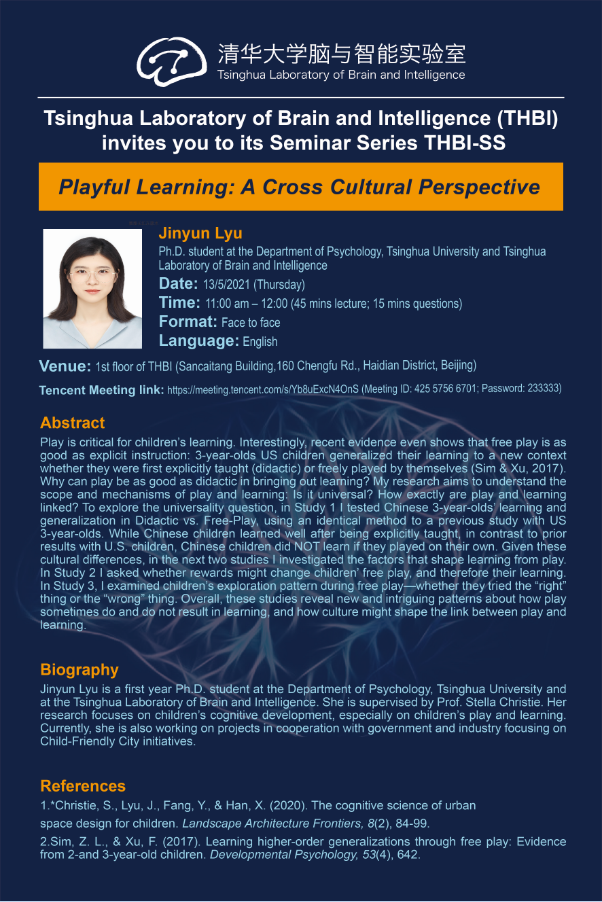

Learning—the process of acquiring new knowledge in order to apply it in future contexts—is a fundamental aspect of our cognition. What does early learning look like? We approach this question by examining young children’s most ubiquitous activity: play. In three studies, we asked whether play results in learning and what mechanisms and constraints govern learning from play.

In Study 1, to investigate whether play results in learning, we compared Chinese three-year-olds’ generalization learning in Free-Play (self-discovery) vs. Didactic (explicitly taught) conditions (N= 59; Mage = 3.25 years, SD = 0.49). Children saw a novel machine that made a sound when certain blocks were put atop it. A rule governed the sound activation (e.g., same-shape rule: the machine was activated if the block’s shape matched the machine’s). The question was whether children could learn and generalize this rule. Children in the Didactic condition were explicitly shown which blocks activated the machine (without being told the rule) while children in the Free-Play condition were simply given the machines and blocks to play with for 5 minutes. Following this, children in both conditions were given two tests: to select one of three blocks to activate a previously seen machine (First-order generalization) and a new machine (Second-order generalization). Children learned well in the Didactic condition: 77% correct in the First-order test (t-test against chance .5, t(29) = 3.40, p =.002), and 73% correct in the Second-order test (t(29) = 2.84, p =.008). However, children did not learn from Free-Play: accuracy of First-order test was 55% (t(28) = 0.55, p =.586), likewise for Second-order test (Maccuracy = 48%, t(28) = -0.18, p =.856). These results differ from a previous study using an identical paradigm with US three-year-olds (Sim & Xu, 2017), where generalization learning was equally high in both Didactic and Free-Play conditions. That is, we found that by three years of age, cultural difference had already influenced learning from play.

To investigate the mechanisms and constraints of learning from play, in Study 2 we ran another Free-Play condition (N=31), but this time with the promise of reward (“Play on your own; if you figure out how this machine works, you’ll get a gift!”). Reward had no impact, as accuracy for First-order (39%) and Second-order (45%) tests were again at chance. In Study 3 we tested whether children’s own hypotheses (about which block activated the machine) impacted learning. To do this, we manipulated whether the child’s first try during Free-Play led to activation (First-Positive-Evidence, N=30) or not (First-Negative-Evidence, N=30). Surprisingly, children could learn the rule from play if their first try was successful; accuracy across two tests were 77%, comparable to Study 1’s Didactic condition. However, children did not learn the rule if their first try was negative .

Across three studies, we found evidence that play could result in learning and generalization, even as well as learning from explicit instruction. However, culture and the child’s own hypotheses may constrain learning from play. We are currently doing experiment four to explore why positive first evidence works but negative first evidence don’t.

Selected publication:

Presentation: